By Farhan Ullah Khalil

Email: khalilfarhan87@gmail.com

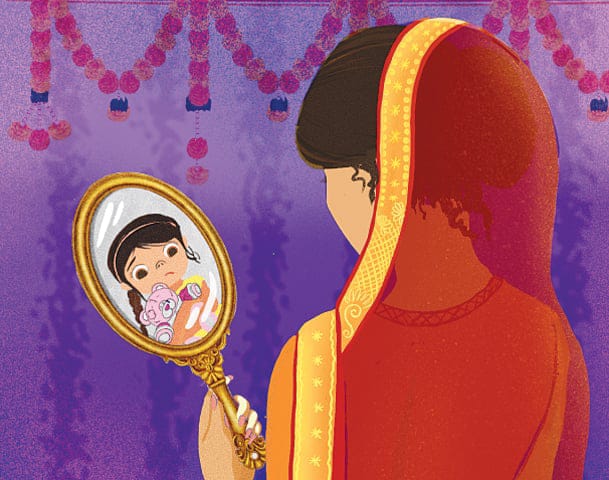

Child marriage in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa remains a deeply rooted yet largely silent social crisis, sustained for decades by tradition, poverty, lack of awareness, and weak legal enforcement. While such marriages are often portrayed as private family decisions, their consequences extend far beyond the household, affecting individuals, communities, and the future of society at large. The lives of underage children particularly girls are shaped by decisions made without their consent and without any planning for their physical, emotional, or educational well-being.

According to the Child Protection and Welfare Commission, more than 200 cases of child marriage have been officially reported since the commission’s establishment. These figures alone dispel the notion that child marriage is exaggerated or rare. However, social experts argue that reported cases represent only a fraction of the real situation, as the majority remain hidden due to fear of social stigma, family pressure, and the influence of local power structures. As a result, child marriage has become a crime that occurs openly yet remains largely invisible.

Data released by Group Development Pakistan further highlights the severity of the issue. The statistics reveal that 26.3 percent of marriages in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa involve individuals under the age of 18, while 6.4 percent occur below the age of 15. These numbers indicate that nearly one in four children in the province is subjected to marriage at an age when they should be in school, not burdened with adult responsibilities. The impact of such early marriages often follows them throughout their lives.

The trend is more pronounced in rural areas, where the prevalence of child marriage reaches 27.4 percent, compared to 20.9 percent in urban centers. In rural communities, poverty, lack of education, traditional norms, and limited legal awareness play a decisive role. However, urban areas are not immune. There, child marriage is often driven by social pressure, misguided notions of family honor, and distorted cultural or religious interpretations.

Poverty is frequently cited as the primary justification for early marriages. Many parents believe that marrying off a daughter at a young age reduces their financial burden. In reality, such decisions replace one hardship with another. Education comes to an abrupt end, dreams remain unfulfilled, and a young girl is suddenly forced into responsibilities for which she is mentally, physically, and emotionally unprepared.

Health experts warn that child marriage, followed by early pregnancy, poses serious risks to girls’ health. Complications during childbirth, anemia, mental stress, and higher maternal and infant mortality rates are common. Young mothers often suffer lifelong health issues due to malnutrition and lack of access to adequate medical care.

The consequences of child marriage are not limited to girls alone. Boys married at a young age are often compelled to abandon their education and enter the labor market prematurely. Most end up in low-paying, unsafe, and unskilled jobs, reinforcing a cycle of poverty that continues from one generation to the next.

From a legal perspective, the situation in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is particularly alarming. The province still relies on the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, which prescribes a maximum punishment of one month’s imprisonment or a fine of only one thousand rupees. In today’s context, such penalties are neither deterrent nor effective. While Sindh, Balochistan, Islamabad, and Punjab have enacted modern legislation to combat child marriage, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa continues to depend on an outdated colonial-era law.

Legal experts emphasize that when punishments are minimal and enforcement mechanisms weak, preventing such crimes becomes nearly impossible. In most child marriage cases, there is little accountability—nikah registrars are rarely questioned, parents or guardians face no serious consequences, and effective monitoring systems at the local level are virtually nonexistent.

The 200 reported cases by the Child Protection and Welfare Commission indicate that the institution is attempting to fulfill its mandate. However, limited resources, restricted authority, and legal complexities severely hinder its effectiveness. Social activists argue that with enhanced powers, adequate funding, and legal protection, the commission could serve as a strong barrier against child marriage.

Awareness campaigns play a crucial role, but experts agree that awareness alone is insufficient. Without strong laws and impartial enforcement, child marriage will persist. Religious scholars, educators, media, and civil society must collectively convey a clear message: child marriage is neither a religious obligation nor a socially acceptable tradition.

Education specialists stress that prioritizing girls’ education and providing financial and social support to keep them in school can significantly reduce child marriage rates. Education not only raises awareness but also empowers girls to make informed decisions about their own lives.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa stands at a critical crossroads. The province must choose whether to continue along the path of outdated traditions and obsolete laws or embrace progressive legislation that ensures a safe, educated, and dignified future for its children. Strong laws, strict penalties, and effective implementation are the only means to protect future generations from this silent injustice.

Ultimately, child marriage is not merely a legal issue it is a test of collective conscience. If silence prevails today, tomorrow’s children will pay the price by losing their childhood, education, and dreams. The future of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa depends on whether society chooses to stand for children’s rights or sacrifices them in the name of tradition.